Kalaupapa – Shaped somewhat like a fish (the locals say a shark) has its head facing east, its tail in the west and a dorsal fin rising from its back on Molokai’s north shore. That dorsal fin is the nearly flat, ten-square-mile (25.9 sq km) Makanalua Peninsula which juts into the Pacific below the world’s highest sea cliffs. A place of stunning beauty, it’s been blessed by nature’s grandeur, and cursed by humanity’s ignorance and fear.

While this area is generally referred to as Kalaupapa, in fact, Makanalua Peninsula is divided into three districts: The Kalawao district on the eastern edge; Kalaupapa and the settlement of Kalaupapa to the west; with Makanalua in the center.

Inhabited from about 650 AD, the Hawaiians fished the rough surrounding ocean by outrigger canoe with nets and spears for over 1200 years . They also farmed the land, coaxing sweet potatoes, onions and taro from the harsh volcanic soil. With the vines of the sweet potato, their main vegetable, they fed their pigs, which in turn they used to barter with other villagers in the eastern valleys.

While the peninsula was not largely settled, it was traveled much and used extensively. The entire area is divided and subdivided by low rock walls that continue for mile after mile, creating thousands of small lots of every imaginable shape.

There is no written history of the people who built them; historians theorize that they were constructed as pens for raising pigs, as windbreaks for growing crops and possibly as property boundaries and land divisions.

The early Hawaiians built fishing shrines called heiau as places to make offerings for their safety while fishing in the rough waters that surrounded the peninsula. These heiau were platforms built of stone in circular and square shapes. Some of their surfaces are filled with coral, while others have elaborate enclosures lined with flat rocks on which offerings of fish or shells were placed.

Today, the trail from Topside Molokai to Kalaupapa is traveled by mule, by hikers, and on foot by some of the workers at the settlement. There is also a small airstrip at the northern edge of the peninsula, used daily to bring in food, supplies and visitors.

Hugging the nearly perpendicular cliffs, the trail is over three miles (5km) long and descends 1,600 feet (488m) to the peninsula. Along its course are 26 switchbacks that corkscrew in and out of canyons and ravines.

Once a year in the summer, when the seas are calm, a barge from Honolulu anchors at Kalaupapa, delivering thousands of pounds of rice, cases of beer, drums of gasoline and supplies to stock the grocery store and hospital.

Kalaupapa’s reputation as a leprosy colony is well-known. Hansen’s disease, the proper term for leprosy, is believed to have spread to Hawaii from China. The first documented case of leprosy occurred in 1848. Its rapid spread and unknown cure precipitated the urgent need for complete and total isolation.

Surrounded on three sides by the Pacific ocean and cut off from the rest of Molokai by 1600-foot (488m) sea cliffs, Kalaupapa provided the environment.

In early 1866, the first leprosy victims were shipped to Kalaupapa and existed for 7 years before Father Damien arrived.

The area was void of all amenities. No buildings, shelters nor potable water were available. These first arrivals dwelled in rock enclosures, caves, and in the most rudimentary shacks, built of sticks and dried leaves.

Taken after Damien had constructed most of the houses seen here, this photo shows the stark, barren peninsula and settlement at Kalawao in the 1880s.

Folklore and oral histories recall some of the horrors: the leprosy victims, arriving by ship, were sometimes told to jump overboard and swim for their lives. Occasionally a strong rope was run from the anchored ship to the shore, and they pulled themselves painfully through the high, salty waves, with legs and feet dangling below like bait on a fishing line.

The ship’s crew would then throw into the water whatever supplies had been sent, relying on currents to carry them ashore or the exiles swimming to retrieve them.

In 1873, Father Damien deVeuster, aged 33, arrived at Kalaupapa. A Catholic missionary priest from Belgium, he served the leprosy patients at Kalaupapa until his death. A most dedicated and driven man, Father Damien did more than simply administer the faith: he built homes, churches and coffins; arranged for medical services and funding from Honolulu, and became a parent to his diseased wards.

In 1873, Father Damien deVeuster, aged 33, arrived at Kalaupapa. A Catholic missionary priest from Belgium, he served the leprosy patients at Kalaupapa until his death. A most dedicated and driven man, Father Damien did more than simply administer the faith: he built homes, churches and coffins; arranged for medical services and funding from Honolulu, and became a parent to his diseased wards.

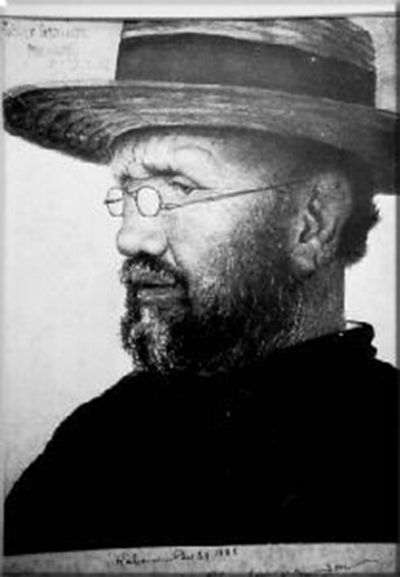

Shown here in a rare pencil sketch from December, 1888, Damien contracted the disease, and after 16 years of selfless service, died in 1889.

In 1886, Brother Joseph Dutton arrived at Kalaupapa to assist Father Damien. Dutton, an energetic and dedicated missionary priest, assumed many of the duties Damien was unable to perform as his leprosy progressed.

Mother Marianne, another revered servant, devoted 29 years on the peninsula as an administrator, nurse and educator. She spent her life on the go, even as her age climbed well into the seventies. She died in 1918.

In 1977, Pope Paul VI declared Father Damien to be venerable, the first of three steps that lead to sainthood. Pope John Paul II declared Damien blessed in 1995, and in October 2009 he will be canonized as a saint.

With the advent of sulfone drugs in the 1940s, the disease was put in remission and the sufferers are no longer contagious. The very few former patients remaining on the peninsula are free to travel or relocate elsewhere, but most have chosen to remain where they have lived for so long.

While Kalaupapa is now a National Historic Site, it is also the home of the few former patients who choose to remain there. So access, is by law, strictly regulated.

Unless you are invited by one of the residents, you must take the tour offered by Damien Tours of Kalaupapa (about $60.00). The peninsula can be reached by air or by way of the trail descending the 1,600-foot-high (488m) cliffs. Visitors can hike in and out at no cost or ride one of the Molokai mules, which will add about $125 to the cost. Visitors must be at least 16 years old.

The peninsula’s terrain is flat: Translated, Kalaupapa means “level land resembling a flat leaf.”

Strong northeast trade winds and a lack of sufficient rainfall make for harsh living conditions. The nearby cliffs receive more than 25 feet (7.6m) of rain annually, but it disappears through the porous ground. At the near edge is the settlement of Kalaupapa, the only town on the peninsula. At the far edge is the district of Kalawao.

Saint Philomena Church in Kalawao was begun as a small chapel by Brother Bertrand in 1872. It was here that Father Damien spent his first nights on Molokai, sleeping on the ground under a Hala tree next to the chapel. The chapel stands today behind the church.

Saint Philomena Church in Kalawao was begun as a small chapel by Brother Bertrand in 1872. It was here that Father Damien spent his first nights on Molokai, sleeping on the ground under a Hala tree next to the chapel. The chapel stands today behind the church.

Father Damien added on to St. Philomena twice, more than doubling its size. To accommodate the needs of his congregation, Damien positioned the church so that the gusty trade winds passed through the many windows.

The interior of St. Philomena was refinished and painted by his parishioners. Because of their fondness for bright colors, they selected a rainbow of colors to complete the task.

In 1995, following the beatification ceremonies in Belgium, a relic of Father Damien was returned to Kalawao and was re-interred next to the church.

Today, St. Philomena stands in homage to Damien the Blessed, the priest from Belgium. A black, concrete cross marks Father Damien’s grave site at Kalawao. It was Damien’s wish to be buried among his people at Kalawao. Finally, his wishes were respected.